As Christmas is approaching, I was reminded of this piece I wrote in 2010. It was only the third post on this blog, and has had the most page views over the years, so I decided that, with a few minor edits and updates, it was worth sharing again.

John Cage, Edwin Morgan and the finding of meaning

Christmas is coming. I can read the signs. There are sparkly decorations in the shops and department stores have started displaying bizarre ‘gifts’ such as electronic talking monkeys that you can clip to your shoulder. (Thank goodness there weren't 'gifts' like that 2000 years ago, or the Three Wise Men might have arrived bearing Gold, Frankincense and Talking Shoulder Monkey...) What else? Oh yes, X Factor fans are thinking about the Christmas Number One. And on Facebook, a campaign against anodyne manufactured pop is once more underway. There’s a group which wants to try and get John Cage’s 4’33’’ onto the Christmas Number One spot. I have to confess, I’ve clicked the Like button.

Born in 1912, John Cage was an American composer, philosopher and artist who became famous for stretching the bounds of music. His 4’33’’ is probably his most famous work. It was composed in 1952, and is for any combination of instruments. The score basically instructs the musicians to not play during the piece’s three movements – it is four minutes and thirty three seconds of absence of instrumental playing. However, it is not four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence, but of environmental noise, of expectation, of aural space.

Cage had been considering the idea of silent music for a while, but was pushed into writing the piece by the example of the artist Robert Rauschenberg, who had produced a series of paintings which were basically large white squares. The point of this was that even if they just looked like blank canvases, they would change according to the conditions in which they are viewed: the quality of the light, or what other colours there might be in the room in which they were displayed. In a similar way, Cage’s 4’33’’ uses the silence as a background canvas for the ambient sound and atmosphere: the sounds to which we are usually too distracted to pay attention. Both Rauschenberg’s pictures and Cage’s music required the audience to pay hyper-close attention in order to experience them. Viewers and listeners had to make an effort: it wasn’t all laid out there in front of them. In fact, this requirement of effort meant that they had to become part of the creative process themselves.

John Cage said ‘I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry’. Edwin Morgan, the Scottish poet who died this year, and whose tribute event, organised by the Poetry Society is taking place at the Southbank Centre, London, on Nov 3rd, took those fourteen words and made his own poem of them. The poem, 'Opening the Cage', is a fourteen line variation of those fourteen words, each line creating new meanings through new combinations.

It takes effort to tease meanings out of these lines, and I’m sure different people will find different things. To me, the first line seems to state the poet’s need to write, his uncertainty about whether that writing has any worth, and the fact that this dilemma is what he is considering:

I have to say poetry and that is nothing and I am saying it

By line 7 the words seem to have assembled themselves into an invitation to strip away all the fripperies of life and perhaps also of language to get to the bare bones:

To have nothing is poetry and I am saying that and I say it

And after a sonnet’s worth of variations, the poem concludes (if a conclusion it is) with the decisiveness of a manifesto:

Saying poetry is nothing and to that I say I am and have it

John Cage was very interested in aleatoric music, the music of chance. Morgan’s poem is very much in that spirit – the randomness of word-shuffling produces chance combinations from which meaning can be derived. Morgan chose the fourteen he felt made the meaning he wanted. It’s an interesting paradox, however, that while the poem is punningly entitled ‘Opening the Cage’, implying the freeing of language and meaning, Edwin Morgan might be considered to have imposed a cage of his own by using the sonnet form. (If it is a sonnet – certainly Don Paterson includes it in his 1999 Faber Anthology 101 Sonnets.) However, a more controlling poet might have added punctuation to clarify the meanings he wished his reader to derive. Morgan does not do this. He lets the meaning of each line stay fluid and free. (Have a look at the similarly constructed 'The Uncertainty of the Poet' by Wendy Cope, a poem also derived from another artist's work, to see how punctuation pins down meaning.) It seems to me, also, that implicit in the poem are all the other possibilities which Morgan did not use. For these reasons the sonnet-shaped cage is only an illusion. It’s a poetic Tardis: the inside is bigger than the outside.

If one accepts this notion, ‘Opening the Cage’ is a poem that could continue, inside the reader’s head, for a lifetime. With 14 words there are 14! (that is, 14 factorial: 14 x 13 x 12 x 11 x 10 and so on down to x 1) possible combinations – in other words, 87,178,291,200 different ways of arranging those words. Well, you might say, some of those combinations will just be gobbledygook. Okay, let’s go for a gobbledygook one: the purely alphabetical

am and and have I I is it nothing poetry say saying that to

Is there any meaning to be found in that? Of course there is, of you look hard enough. The ‘am’ separated from its implied ‘I’ has a plaintive, questioning tone, while the repeated ‘and’s and ‘I’s reinforce this feeling of uncertainty. Then we have the question around which this line revolves, the shaky, inverted ‘is it nothing, poetry?’, followed by an imploring ‘say’ – tell me the answer. Next comes a phrase that implies no confidence in the received answer, ‘saying that to…’. This seems to me to question the motives of the unheard speaker: You’re just saying that for some other motive. Whatever it is, it means I can’t rely on your answer to help me in my search for whatever I’m searching for.

And I’ve derived that ‘meaning’ from listing those fourteen words alphabetically. You, dear reader, might derive a completely different meaning – it’s up to you. All it takes to derive meaning is a reader with the willingness to do so.

|

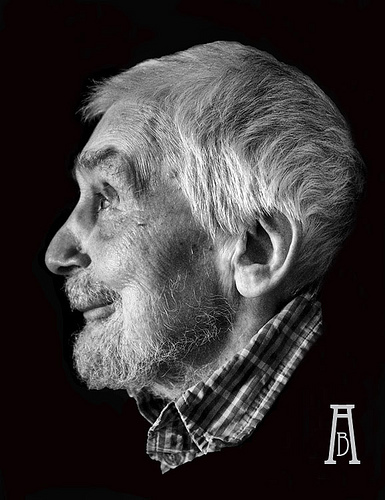

| "Edwin Morgan by Alex Boyd" Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 via Commons. |

This kind of poetry, poetry that demands so much of the reader’s participation in the act of creativity, reminds me of the writing of someone I once met in a critique group. She was severely dyslexic, and had come to poetry, and literacy in general, quite late in life. For her, her poetry was mostly therapeutic, but for her readers, it became something quite exciting by virtue of her dyslexia. I can’t give any actual quotes, because I’m not in touch with her now, but, for example, in a poem about domestic violence, she might write things like ‘meating’ instead of ‘meeting’, and ‘burned’ instead of ‘born’ – changes which often added a startling and completely unintended complexity to her poems. When she was alerted to this, she was often delighted with the effect that she had created, and would let it stand. Her meanings were created in an aleatoric way, and the initially chance significances found by her readers were then fed back into her later revisions of the poems.

I’m not sure that Cage’s 4’33’’ will make the number one spot*. Nearly sixty years after it premiered it still provokes angry responses, as can be seen by some of the comments on the Daily Mail's coverage of the Facebook campaign. One person even rants about how the people who support the campaign should be locked up. What amuses me, though, and would probably have pleased both John Cage and Edwin Morgan, is the fact that the Cage piece must have suggested itself for this year’s campaign simply because of its chance sonic relationship with last year’s successful campaign band. Rage Against the Machine – Cage Against the Machine. A chance rhyme from which such appropriate significance and meaning has been derived. How could it have been anything else?

The making of Cage Against the Machine, 2010.

*In fact, Cage Against the Machine made it to number 21 in the UK Chart Singles. X Factor's Matt Cardle took the Number 1 spot with When We Collide. Hey ho, never mind.

‘Opening the Cage’ can be found in 101 Sonnets, ed Don Paterson, Faber 1999.

No comments:

Post a Comment